|

|

----------------- Amelia Earhart Amelia Earhart, American aviatrix

- Lady Lindy, Queen of the Skies, First Lady of the Air - with her

low-wing twin-engine Lockheed Model

10-E Electra mono-plane. (1936 photo.)

The plane was designed in 1934 and built in 1935. The plane was outfitted

for long-distance flights to Earhart's specifications and delivered to her in July 1936.

In June 1928, Earhart was the first woman passenger on a non-stop flight

across the Atlantic Ocean. (Newfoundland to Wales.) In May 1932, Earhart was the second person to fly solo non-stop across

the Atlantic Ocean, five years after Charles Lindbergh's pioneering

solo flight from New York to Paris in 1927. Earhart flew from Newfoundland

to Ireland, In January 1935, Earhart was the first woman to fly solo from

Honolulu, Hawaii to Oakland, California.

1937 The

World Flight A Great Circle Flight Around

the world by the equator Amelia Earhart set out to fly around the

world by the equator - the longest possible

route. Amelia Earhart and her husband, George Putnam (1887 - 1950),

study a map before the flight. The Lockheed Model 10-E Electra. The

photo was taken in Oakland, California in mid-March 1937 or on Wheeler Field on the Hawaiian island of Oahu on March 18, 1937.

Fifteen planes of this model

were built for a pilot, co-pilot, two navigators, and ten passengers. Passenger

seats were removed from two of the planes to carry extra fuel for long flights. Earhart got one of the two planes. Dick Merrill

and Jack Lambie flew the other plane round-trip across the Atlantic in May 1937. Earhart's plane was

outfitted for the round-the-world flight.

The sketch above points out

the Electra's two engines, pilot escape hatch atop the cockpit (one of the

plane's two entrances or exits), the navigator's station, and location of the

extra fuel tanks in the fuselage (between the cockpit and the navigator's station). The antenna of the plane's Radio Direction Finder (RDF), to assist in navigation

by determining the direction to the source of radio signals, was a manual rotatable hoop above the cockpit, called a "loop

antenna". Omitted from the sketch is

the plane's only door, on the port side. There was a lavatory in the back of the plane. The sketch is of the plane as it

looked in mid- March 1937. Photo of the control panel in

the cockpit of Earhart's Electra. Two seats for pilot, left, and co-pilot, right. The box in the upper

left corner has been described in some accounts as a radio compass receiver. If so, the photo was probably taken in Burbank,

Califonria not later than early March 1937, when the radio compass was removed. Amelia Earhart said the round-the-world flight would be her last exploit

in aviation. She wanted to do other things and continue her work for women and education. She would be age forty at the end

of July. Fred Noonan

Frederick Joseph

Noonan, born in Chicago

on 4 April 1893, was considered the best flight navigator of the day. The above photo is of Noonan

with Pan American Airways. In 1935, Noonan was the first to chart many commercial air routes

across the

Pacific. He trained flight navigators

for Pan Am. Noonan's father was from the state of Maine. His mother came from England with her

family. Noonan moved to Seattle and went to sea in his mid-teens. He sailed on American and British merchant ships (mostly

British) - sailing vessels (windjammers) and steam

and motor ships.

During the Great War, Noonan sailed on American

and British merchant ships. He was a ship's officer on American and British merchant vessels after

the war. By age 30 he was a master mariner - the highest rank, equivalent

to a ship's captain on cargo and passenger ships - with the highest ratings. By the 1930s his license was "unrestricted",

for any ship, "any tonnage, any ocean". In the late 1920s, Noonan was drawn to aviation. He got a commercial pilots's license.

He joined an American airline with air routes to South America. The airline was acquired by Pan American Airways. He

was a navigation instructor and managed Pan Am's airports in Haiti, Cuba and Miami. Noonan

was the navigator on the first Pan Am Clipper flight through Latin America to the Pacific, in 1935. He was the chief navigator on all of Pan

Am's Pacific Survey flights in 1935 and first commercial Clipper flights across the Pacific in 1936. He trained Pan Am's Pacific

Clipper navigators. Noonan did not leave Pan Am but stopped working for the airline in late 1936 when its management did not respond to requests to improve working conditions and the pay of flight crews. Pacific Clipper crews were pushed beyond their physical limits (and beyond

the limits set by government regulations). Noonan planned to open a navigation school. In mid-March 1937,

a few days before the scheduled take-off from Oakland, Amelia Earhart invited Noonan to join the World Flight as its celestial navigator. Oakland, California - Honolulu, Oahu, Hawaii The World Flight crew

before taking off from Oakland, California for Honolulu, Hawaii on 18 March 1937. From left to right are Paul Mantz, co-pilot and technical advisor; Amelia Earhart, pilot; Harry Manning,

radio navigator, and Fred Noonan, celestial navigator. Behind

the crew is Earhart's Lockheed Model 10E Electra. Paul Mantz (1900

- 1965) was a famous Hollywood stunt pilot and air racer. Mantz was Earhart's partner in a brief business venture,

the Earhart-Mantz Flying School, in Burbank, which Mantz directed through his airline, United Air

Services, in 1935. Mantz trained Earhart in long-distance flying. Mantz accompanied the World Flight as

Earhart's technical advisor to Hawaii, where he was

to meet his fiancée. Harry Manning (1897 - 1974) was a cargo and passenger ship captain. He was also an air pilot, radio

operator and navigator. He was a friend of Earhart. He was captain of the ship that brought Earhart back to America after

her passenger ride on a non-stop flight across the Atlantic in 1928. As radio navigator on board the World Flight, he

was to guide Earhart across the entire Pacific Ocean - from

Oakland to Honolulu to Howland Island and Lae, New Guinea. Manning was to go as far as

Darwin, Australia. Fred Noonan was a last-minute addition to the crew. A pioneering flight navigator in the Pacific, his knowledge

and experience were extensive. His quick method of calculation simplified celestial navigation in aviation. (Most celestial

navigators estimated their position from observations of three stars. Noonan was known for two-star position fixes.) A

radio operator and celestial navigator were essential for any flight across the Pacific Ocean. It would be dangerous to attempt

the flight without either. Radio was not always reliable. Initially, Noonan was asked to assist Manning in navigating Earhart

from California

to Honolulu

and Howland - the latter flight a long and difficult stretch over the central Pacific. Manning was

not familiar with multi-engine planes and not experienced in long-distance flying or cross-Pacitic flights. Noonan was to

get off at Howland and return

to California with the Coast

Guard. In

Honolulu, Earhart wisely invited Noonan to continue from Howland to Lae. He was to get off with Manning in Darwin.

Earhart would continue the flight alone from Darwin, fly across Asia,

Africa, the Atlantic, South America, the Caribbean and the U. S. back to California. Earhart billed her World Flight as a scientific expedition and her plane a "Flying Laboratory". In reality, the plan and the flight were nothing of the sort. The claim was a device to obtain

sponsorship from an academic institution. In the back of the plane were stations for the radio and celestial navigators, extra

fuel tanks. and emergency provisions. Paul Mantz, Amelia Earhart and George Putnam Loading the plane in Oakland on 17 March 1937 The Hayward Review

(San Francisco Bay), 23 February 1937. Map shows the planned route of the flight from Oakland, California around the world to the west, starting out across the Pacific.

Six fuel tanks, including four extra large tanks -

three big tanks, shown in the photo above, and one slightly smaller tank - were in the cabin between

the cockpit and the navigator's station. The photo was taken probably in February or early March 1937. The navigator could

climb over the tanks to get to the cockpit or attach notes onto the end of a

long stick, reach over the fuel tanks and hold

it out to the cockpit. Earhart is atop the fuel tanks with a radio that has been described in

some accounts as a radio compass receiver (a navigation homing device). If so, it was removed before the flight. The

radio has been described also as a radio transmitter. (See below.) On 18 March 1937, Earhart, with a crew of four, flew

the first leg of the World Flight from Oakland to Honolulu. There was one technical malfunction during the flight. The

right engine shut down temporarily. Honolulu Paul

Mantz, as the co-pilot, landed the plane at Wheleer Army Air Field, the army's pursuit (fighter) plane base in

northwestern Oahu, on 18 March.

The crew on Oahu on March

18, 1937. From left to right: Manning, Mantz, Earhart and Noonan.

Mantz checked the Electra. There was a problem with the right engine propeller that would have to be repaired.

The next two legs across the Pacific would

be the longest, most difficult and most dangerous of the entire World Flight. No one had flown between Honolulu, Howland and

Lae before. This was a pioneering venture.

The next leg of the flight was to Howland Island, a tiny remote island in the central Pacific.

Earhart and Mantz visited Luke Field, the US Army's main air base on Oahu (for pursuit

planes and bombers), on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, and decided its runway would be better than Wheeler Field for the

take-off for Howland. The army shared the island, dividing

it in half with the navy, which had its base in Pearl Harbor.

The next day, 19 March, Mantz checked the plane again and took it on a 45-minute test

flgiht over Honolulu.

The

Electra on Wheeler Field. The photo was taken on 19 March, with Paul Mantz (and his fiancée and a friend) on board, before

Mantz tested the plane in flight.

Mantz landed the plane on Luke Field. Further

checks and corrections. There was a problem during refueling. Noonan impressed Earhart and after the flight

from California to Hawaii, Earhart asked him to consider accompanying her the entire flight - across

Asia, Africa and the Americas. The plane would take off before dawn on 20 March for the 11 1/2 to

12-hour-flight in day-time to Howland. On

board with Earhart were Manning and Noonan. The plane was heavily loaded with fuel for the long flight. Earhart,

with Manning as co-pilot, began the night take-off. The plane, with Earhart at the controls, ground-looped on the take-off and crashed. Earhart's Electra after

its crash on Luke Feild on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor on 20 March 1937. There

were no injuries to the crew of three. There were numerous accounts of the crash.

As the

plane accelerated on the take-off roll the left engine

seemed to rotate faster than the right. The plane swayed to the right and headed off the runway. The plane swerved towards

the left and tipped over on its right. The right wing may have clipped the ground. The plane slid sideways down the runway.

The right landing gear collapsed and the right tire burst. Then the left landing gear collapsed. The plane

spun to the right, slid and whirled on its belly down the runway, and came to a stop facing the opposite direction of

the take-off. Earhart

was not sure what caused the accident. She thought the right shock absorber might have collapsed. A tire might have burst.

In a telegcam to Putnam, Mantz said a tire

burst. That same day, Noonan wrote an article for United Press:

He was in the back of the plane at the navigator's station. A tire burst. Taking off with one tire would have necessitated

a crash landing on Howland or a ditching at sea. Earhart controlled the plane, brought it to a stop and limited the damage. Earhart

planned to try again.

The plane was shipped back to Burbank

for repairs.

Manning would not be available for another attempt. His leave from the

shipping company would soon expire. Due to the seasonal change of direction of the winds in the Pacific, the

second attempt around the world would be to the east, starting out from California and flying across the

southern U. S., rather than west over the Pacific. There may have been other reasons

for the change in direction. According to some accounts, there was a possibility the government would ban the flight if

it started again in California and Honolulu. On the second attempt, Earhart was to be accompanied over the entire route by Fred Noonan.

Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan in Honolulu after the crash of the Electra, on board the SS Malolo

to San Francisco. Silent

film footage

The Second Attempt On 20 May 1937, Amelia

Earhart set out again on the World Flight. The Putnams lived in the city of Burbank, a suburb of Los Angeles, and

Earhart flew north to Oakland (a large city across San Francisco Bay from the San Francisco Peninsula) in the morning.

Earhart flew back to Burbank in the afternoon on the first leg of the flight (its official start). An engine fire during

refueling delayed the flight in Burbank to the next day. Take-off from Oakland Official start of the World Flight Features Earhart, San

Francisco Bay, and George Putnam in Burbank

Film of Amelia Earhart’s Take-Off Just before the take-off Uploaded by the WSJ in 2015

Fred Noonan was

twice married, the first time in 1927. He had recently remarried. The above photo is of Noonan with his wife,

Beatrice Mary. The couple lived in Oakland. The photo was taken at the airport in Oakland on 20 May or in Burbank on 20 or 21 May 1937.

Earhart,

Putnam, Noonan and a mechanic took off from Burbank on 21 May. They flew east for Miami, Florida. Miami At night, Noonan navigated

the plane across the Gulf of Mexico from New Orleans to Miami. Earhart, Putnam,

Noonan and the mechanic arrived in Miami at dawn on 23 May. The plane landed at the wrong airport. It was closed for the night. In landing at the right

airport shortly afterward, Earhart misjudged her height over the runway and damaged a wheel strut. Amelia

Earhart's Last Flight Documentary (2000) Part

1 of 4 This documentary is about a recreation of Earhart's flight around the world

sixty years later, in 1997. This part, the first fifteen minutes, recollects Earhart's preparation for the 1937 flight.

Earhart and Noonan remained in Miami ten days while numeous changes to the plane were made. The external

changes are known but there is uncertainty about the reported changes to the plane's radio system.

The plane was built in mid-1936 and refit for Earhart with

a single plexiglass window on each side in the back for the celestial navigator to make observations of the sun, moon and

stars. A

second and larger window was added farther back to the starboard side of the

plane, as shown in the photo above taken in a hangar in Burbank. The second window may have been in the lavatory. This window was removed (patched) in Miami before Earhart and

Noonan set out across the Caribbean. The photo above shows the starboard side of Earhart's Lockheed Model

10-E Electra as it looked before the second window on the starboard side was

installed or after it was removed. Thus, in the back of the plane there were two windows, one on each side, and a third window,

in the door, which was on the port side of the plane. The navigator sat at a desk in the back of the plane to make observations through the

windows. An audio intercom system was not on board. The

navigator could check his observations from

the cockpit. Noonan was also a pilot and probably spent much of the World Flight in the cockpit. On 1 June 1937, Earhart and Noonan took off from Miami

for the Caribbean and South America.

They were to fly a path east along an equatorial

route, circling the world as close to the equator as possible. A Great Circle flight. Excerpt from a documentary

Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan at Parnamerim

airfield, Natal, Brazil, 7 June 1937

St. Louis, Senegal

The flight across the Atlantic -

from Natal in Bahia in Brazil to Senegal - took 12 to 13 hours.

In a letter, Noonan wrote that heavy rains and thick clouds

blinded them for ten hours. The African coast was socked in. The radio was knocked out. They got through, Noonan wrote, by

their "usual luck". The destination was Dakar.

Noonan's chart of the flight, which was sent back to the U. S., showed a planned flight

path from Brazil direct to Dakar - and another flight path, leading to a point on the African coast

several miles to the east and slightly south of Dakar. From this point the chart indicated a turn to the north, by-passing

Dakar, and a continuation to St. Louis,

Senegal, 100 nautical miles farther up the coast to the north of Dakar.

According to a press

release, Earhart landed in St. Louis because Dakar was covered by haze.

According to Earhart's

dispatch to the Herald-Tribune, she sighted

the African coast in heavy haze. Noonan told her to fly south. This would have brought her to Dakar within a half-hour, she

said. Instead, she followed the urge to fly north and soon saw St. Louis. By then, it was too late in the day to turn

round for Dakar.

It has been suggested Earhart chose to land in St. Louis,

which was the regional hub of Air France, to better service the plane.

Earhart and Noonan flew to Dakar the next day.

Fred Noonan and Amelia Earhart in Dakar, Senegal

on 8 - 10 June 1937.

Earhart and Noonan, left of the table, at the Aero

Club in Dakar, Senegal.

Earhart and Noonan at the Aero Club in Dakar, Senegal.

Java

Fred

Noonan in Bandung on Java

in the Dutch East Indies in

late June 1937.

Darwin, Australia

Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan, on the right

in the above photo, in Darwin, Australia on 28 - 29 June 1937.

Parachutes are on the ground.

George Putnam wanted his wife to hurry home

for the 4th of July. He had made preparations for her to attend a radio event. Earhart

and Noonan took off from the port of Darwin in the Northern Territory of Australia on the morning of 29 June. They flew to the

port town of Lae at the eastern end of the island of Papua - at the time administered by Australia

as the Territory of Papua - and landed at 3:00 p.

m. The flight, 1,040 nautical miles (1,200 statute miles), took seven hours and forty-three

minutes.

Lae, New Guinea Amelia Earhart and her Electra arrive in Lae, New Guinea

on 29 June 1937.

Map charting the path of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan on their

round-the-world flight by the equator in 1937. Departing from Oakland, California on 20 May and Miami, Florida on 1 June,

they flew across the Caribbean Sea, the northeast coast of South America, the Atlantic, Africa, the southern coast of Arabia,

the north of India (Karachi and Calcutta), Southeast Asia (Burma, Siam, British Malaya and the Butch East Indies), and arrived

in Darwin, Australia on 28 June and Lae on Papua on 29 June. They took off from Lae at noon on 2 July

and headed east for the central Pacific. Earhart and Noonan had flown three-quarters

of the way around the world. The next three legs of the World Flight would be the last. This would

be the longest stretch of the flight, totalling 5,966 nautical miles (or 6,866 statute

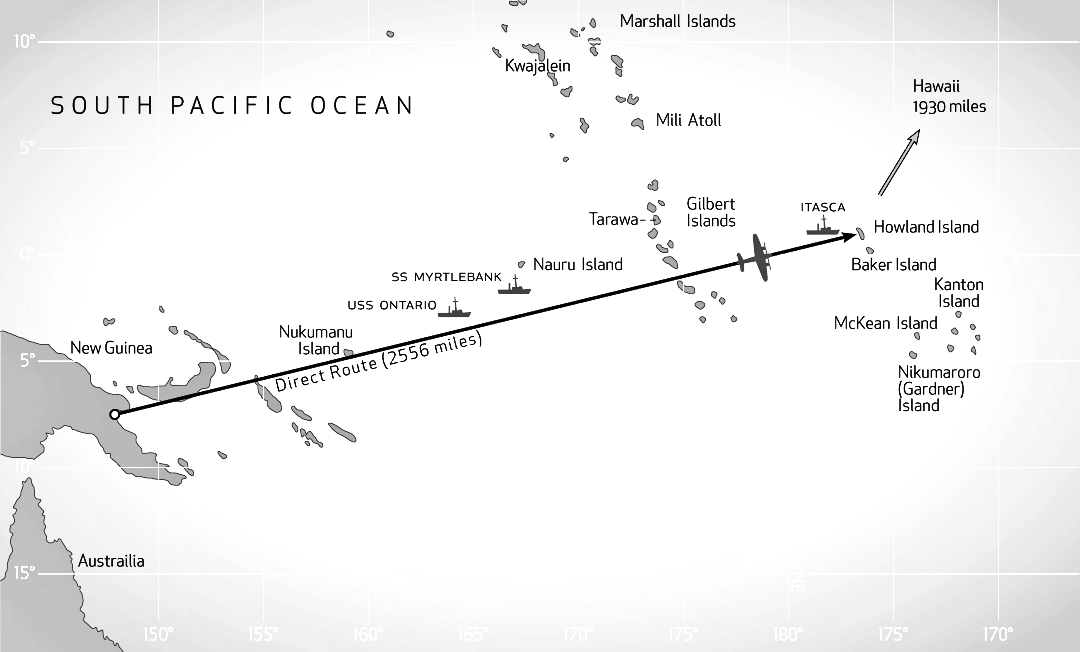

miles): 1. Lae to Howland Island - 2,221 nautical miles or 2,556 statute miles (almost entirely

over water); 2. Howland to Honolulu - 1,651 nm or 1,900 statute miles (the entire flight over

water); and 3. Honolulu to Oakland, California - 2.094 nm/2,410

miles (the entire flight over water). The next two legs -

from Lae to Howland and Howland to Honolulu - would be the most difficult and most hazardous of the

entire flight. No plane had flown between those points before.

The flight from Lae to Howland would be the most difficult

of all.

Howland Island (in the middle of the globe above) is just north of the equator and about 200 nautical

miles east of the 180th Meridian, the International Date Line (IDL). Earhart wanted to depart for Howland the next day, 30 June. With

all that had to be done, however, that would not be possible. There are numerous accounts of Earhart's and Noonan's preparations

in Lae for their flight to Howland. There are Earhart's letters, telegrams and a dispatch to a newspaper; Putnam's telegrams; US Navy and Coast

Guard telegrams; messages logged by radio operators; and reports by two persons directly involved in Lae. The telegrams

and reports are often cited as the most important accounts. A report was presented with a letter by Eric Chater, manager of Guinea Airways in Lae, to the San Francisco

office of a mining company involved in gold mining in New Guinea, on 25 July 1937. The letter was found in the company's office

files in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1992. Chater sent a report also to Putnam. At the time, in 1937, Lae was a

gold rush town, at the centre of gold mining operations, with a busy airfield and many planes and pilots. Another report was presented by a government official, James A. Callopy, the local district superintendent

for civil aviation, in a letter to his superior, on 28 August 1937. Callopy's report and Chater's report to the gold mining company differ in their descriptions of

Earhart's take-off from Lae and radio messages during the first seven hours of the flight. Earhart had dinner with the Chaters at their home in Lae. Noonan passed the evening with Callopy and

another pilot. At

6:30 the next morning, on 30 June, Earhart sent a telegram to Putnam, in Oakland, California, to inform him of a delay:

"Radio misunderstanding

and personnel unfitness. Probably will hold one day."

The telegram

requested a weather forecast from Howland (or Honolulu) and, also, a meteorological report from Howland

for Noonan. There

should not appear to be any reason to dwell on this telegram. There was some question about radio procedures

that should be answered in a day or so. The crew were fatigued and needed another night's rest. Decades later cranks made much of the telegram to spread malicious gossip. Thus, it cannot be omitted

from an account of Earhart in Lae. There were numerous problems with the plane during the journey

from Natal to Lae. Radio was the biggest problem. Radio is considered to have determined the outcome of the flight across the Pacific. The plane was often without radio contact as it flew around the world. The pilot followed

the magnetic compass and geographical features. The navigator estimated their position by celestial observations (the

sun, moon and stars) and dead reckoning (a calculation of distance from point

to point by the time of the run, the speed of the plane and the speed of the winds). Over the vast Pacific Ocean, without

recognisable geographical features, the absence of radio contact could doom a flight. Earhart's telegram to Putnam applied to the next

leg of the flight, from Lae to Howland Island, and "radio misunderstanding" implied a lack of agreement over

radio broadcast schedules, signals and frequencies with radio operators along the flight path. It was often said that Earhart did not understand sufficiently her radio and the use of radio in general

- and that she did not care enough about it. Over the Pacific this could be fatal.

If there was a "radio misunderstanding",

it was at Earhart's end. Earhart was ill with dysentery five days earlier. Her telegram implied that the crew were not well.

Noonan was in good health throughout the venture. If someone was unfit, it was Earhart and her unfitness may have impaired her judgement in the week before

the flight. From

Lae to Howland Island, Earhart was to be in contact with three radio stations, each at a different point. The first was the Guinea Airways

radio station at the point of departure on the airfield in Lae. The second was the USS Ontario, a naval vessel stationed as a radio beacon in the open sea at mid-point

along the flight path to Howland. The third was at destination, Howland Island, where the US Coast Guard Cutter Itasca was stationed

on "plane guard" and to serve as a radio beacon and, if necessary, guide the plane to the island. This was a radio agreement that

would not - or could not - be followed to the extent required. A US government official on Howland,

Richard Blackburn Black, was the Putnams' personal contact and representative on the Itasca and Howland Island. Black

was responsible also for all arrangements on the Itasca, Howland and the flight path across the Pacific from Lae

to Honolulu. He relayed telegrams to and from the Putnams. Radio

There are many accounts of the radio systems

on board the plane. They differ considerably. The systems were changed at least once in the U. S. and some modifications may

have been made en route. The plane had a radio

transmitter, receiver and navigation aid. Each had its own antenna

or antennae. Their specifications and capabilities are unclear, however. During the flight from Lae to Howland, sporadic messages were received from the plane in the first seven hours and last five hours. It is possible the radio receiver did not work until the last hour. Or

Earhart did not care to acknowledge messages until then. In the end, only

the navigation aid - a homing

device that never worked during the entire journey - could decide the fate of the crew. How the radios and antennae were selected, removed, replaced or modified

in the U. S. and en route is not clear. Numerous experts were consulted. In some accounts, Lockheed delivered the plane in July 1936 with a Western

Electric Company radio transmitter and receiver and the Bendix Corporation replaced them in 1937. By some accounts, Earhart

and Putnam received $5,000 from Bendix, one of the World Flight's sponsors, to remove the Western Electric equipment and install

Bendix equipment to advertise the company. A radio technician in Darwin reported all radio equipment on board was Bendix.

It is generally accepted, however, that a

Western Electric transmitter and a Bendix receiver were

on the plane in Lae. As in March, before the crash in Honolulu, there were three antennae -

for transmitting, receiving

and navigation. A telegraph set could be plugged into the transmitter to tap out signals in Morse Code on a key by

hand. A telephone (microphone and earphones)

could be plugged into the radio (transmitter and receiver) for broadcasts and two-way communication by voice. The navigation aid, a

homing device installed by Bendix, was an antenna in the shape of a hoop called a "loop antenna", above the cockpit, for finding the direction

of radio signals transmitted by a beacon. The loop was connected directly to the radio receiver in the cockpit. One or

two more antennae may

have been used for

the purpose.

Sketch

of the Electra during the first attempt of the World Flight in March 1937 shows the Bendix Radio Direction Finder, a manual

rotatable loop antenna atop the cockpit; the radio receiving long wire antenna under the fuselage; and the radio transmitting

wire V-type antenna atop the fuselage. This sketch omits the port-side door. Accounts of the 50-watt transmitter's specifications differ, probably because some believe it was made by

Western Electric and others by Bendix. There were reports that the original Western Electric transmitter was replaced

by another Western Electric transmitter in February 1937. The transmitter had at least three separate bands (or channels). It may

have had six. One band covered a range of low frequencies

from 325 - 500 kilo (k) cycles (c) per second (s) - kcs. This band was used in maritime and aeronautical radio navigation. A low frequency was any frequency on or below 1500 kcs. (200-metre wavelength). A high frequency was any

frequency 1500 or above. The lower the frequency the longer the wavelength. The higher the frequency the shorter the

wavelength. There are advantages and disadvantages to both. Generally, longwave - low frequency

- travels farther and provides better reception. Shortwave - high frequency

- is often better during the day. Pilots contacted the ground on a low frequency. Pilots contacted each other

over short distances on a high frequency by radio telephone. Two bands, for broadcasting, covered a range of high frequencies from 2500 - 6500 kcs., with one band

for frequencies around 3000 and the other around 6000. Some believe the transmitter had only three bands and they were fixed

("crystal-controlled") to one frequency each - 500, 3105 and 6210 - but could

be calibrated to other frequencies prior to flight.

Others beleive each band could be tuned to various frequencies in flight. The radio transmitter's antenna was a long wire strung across the top of

the fuselage to the tail wings in a triangular V shape, known as a V-type antenna. It was called also a "fixed antenna". It

could not be adjusted in flight. (See sketch above.) According to some accounts

the Western Electric radio receiver delivered with the plane in 1936 was replaced by Bendix before or after the crash in Honolulu

in March 1937. The Bendix radio receiver has been described as an "all-wave" receiver

with four separate bands, each with a different range of frequencies. Two bands for low frequencies: 188 - 420 kcs. and 485

- 1200 kcs. Two bands for high frequencies: 1500 - 4000 kcs. and 4000 - 10000 kcs. Each band could be turned to various frequencies

in flight. By some accounts, the receiver had five bands, the first three

bands to 4000 and the fourth and fifth bands from 4000 to 10000. By

other accounts, there were six bands, covering a range of frequencies from 150 to 15000 kcs. The first three bands were

for low frequencies 150 to 315, 315 to 680 and 680 to 1500. The last three bands were for high frequencies 1800 to 3700, 3700

to 7500 and 7500 to 15000. The receiving antenna was a long wire strung under the belly

of the fuselage. It was called also the "trailing antenna" (TA) - the long wire trailing under

the fuselage. (See sketch above.) Transmitting and receiving low-frequency signals -

longwave - require longer antennae. The receiving antenna was reeled out in series, mechanically or

by hand, after take-off and reeled in before landing. Apparently, its length could be adjusted in flight to receive a certain

high or low frequency. Some believe the TA was destroyed in the crash in Honolulu and

not replaced. Others believe a new wire antenna was installed but removed later in Miami or some time before Lae. There

were reports that it was shortened in Darwin. Some believe it was on the plane in Lae. Some believe Earhart removed it entirely

and used the transmitting wire V antenna atop the fuselage for both transmitting and receiving. Some believe Earhart

used the radio direction finding loop antenna also

as a receiving antenna. Some believe there were two seperate receiving wire antennae on the plane in

Lae - an adjustable long wire (TA) for low frequencies and an adjustable short wire for

high frequencies, both under the fuselage. Some believe the long wire was removed and only a short wire was in place,

either adjustable if under the fuselage or fixed if on one side of the fuselage. Some believe there was only a short fixed

wire under the plane in Lae. In general, the plane transmitted and received on

the low frequency of 500 and the high frequencies of 3105 kcs. and 6210 kcs. The radio

could receive on any frequency. In the U. S., 3105 kcs. was the common aeronautical calling and working

frequency and 6210 kcs. was an alternate frequency for use only during the day. Earhart preferred the higher frequency by

day. All ships at sea kept watch for signals in Morse Code on 500 kcs. - the international

initial contact and emergency distress frequency. Ships made contact on 500 kcs. and agreed to continue on another low frequency.

Long

tones or signals in Morse Code on low frequencies, usually around or below 500, were used by ships also for navigation

- finding the direction to the source of radio signals. Thus, it was particularly important for a plane flying over the ocean, especially the vast Pacific,

to transmit and receive on 500 kcs. and other low frequencies. The ability - or inability -

to transmit and receive on 500 kcs. and other low frequencies -

would be seen as the crux of the communication matter on the flight across the Pacific. The plane's radio transmitted and received Morse Code signals by telegraph

on 500 kcs. It was possible to transmit messages by voice over the radio telephone

on 500. Generally, 500 kcs. was for Morse Code. Signals in

Morse Code sent by telegraph were much more reliable and travelled much farther than messages by voice over the radio telephone.

By some accounts, the long receiving wire antenna (TA) contained a "loading

coil" that received 500 kcs. By some accounts, Earhart removed the long receiving wire antenna

(TA) and shortened the transmitting V antenna, thus giving up her radio's 500 kcs. and low frequency capability,

and discarded the plane's telegraph sets because she did not know Morse Code. Earhart had a radio licence that

required proficiency in the use of Morse Code and communication by voice. In telegrams, Earhart instructed radio operators

to transmit

messages to her in Morse Code at the rate of 15 words per minute. For some reason or other, before the departure from Lae,

the US Coast Guard, responsible

for the "plane guard" on

the flight path, doubted

Earhart's ability, questioned her instructions and decided to reduce the rate to ten words per minute. The change may have

been prompted by Putnam. Paul Mantz was to train

Earhart in the use of her radio. It was said, however, that Earhart cut classes to attend publicity gatherings. Apparently, Earhart had to renew her pilot's licence in the U. S. just before her first attempt on the World

Flight and persuaded officials or the examiner to forego the radio and flight tests before certifying her.

In any case, ships at sea often replied in Morse Code at the slow rate of two words

per minute. Like most pilots, Earhart preferred communication by radio telephone. It

was often impractical for a pilot to tap out and write

out messages in Morse Code, especially during turbulence.

Some believe that without Harry Manning, who was to have been the plane's radio

operator, Earhart felt the telegraph sets were useless and dead

weight.

If so, Earhart was living in the future. Morse Code was widely in use and the most common way to communicate at sea

and in the air over the sea. When weather conditions interfered with celestial observation and dead reckoning the radio was essential. In bad weather, Morse Code signals by telegraph were

much more reliable than voice by the radio telephone. If Earhart could not transmit messages by telegraph, she could send signals

in Morse Code over the radio telephone by playing with the microphone switch. She could hold the switch down to produce a

long tone.

There were claims also that Noonan did not know Morse

Code. This is unlikely. Noonan had many years of experience at sea and in the air. He was a licensed captain of ships. He

had a commerical airplane pilot's license. As required of air pilots, Noonan had also a radio licence that required proficiency

in the use of Morse Code and communication by voice. Noonan could send and read 16 to 20 words per minute in Morse Code. In

1937, a professional radio operator in the U. S. was required to transmit and receive at least 25 words per minute in plain

text. Noonan had his own Morse key set but, as far as is known, a telegraph

set was not on the plane in Darwin and Lae. No one recalled seeing a telegraph set on board. The transmitter and receiver could not be operated simultaneously. The radio operator switched the radio

from one to the other - from the transmitting wire antenna to the receiving wire antenna. Both had

separate relays to the radio in the cockpit. The loop antenna, however, was connected directly to the radio receiver,

through its own relay and operated by a separate switch. Radio navigation device The plane's radio navigation aid - a homing device known as a "radio direction finder" (RDF) -

was used on land, in the air and at sea. This instrument detected the direction of radio signals to assist a plane in navigating to its

destination. Details of this device on

Earhart's plane, especially its capabilities, are

unclear.

Radio

compass Initially, Earhart had a Bendix radio compass, designed

in 1935 and installed in October

1936. The

radio compass system indicated the direction to the source of radio signals. The radio compass had its own receiver. The radio compass system required

two antennae. The radio compass

was connected to a short fixed wire antenna, called a "sense" (sensitive) antenna,

on the

port side of the fuselage, by which the radio operator listened to the radio signals. This sense antenna was "non-directional"

- it did not indicate the direction of the signals. The radio compass receiver was connected

also to a manual rotatable direction-finding antenna - a small loop within a "streamlined" housing -

above the navigator's station in the cabin. The loop antenna indicated the directions of the signals on a 180-degree

baseline but not their source. The radio operator switched from

the sense antenna to the loop antenna or listemed to both simultaneously (it is not clear which). The combination of the sense

wire antenna and loop antennae (DF) enabled the radio operator to determine the exact direction to the source of the signals.

In 1937, the system was not yet "automatic". (Source: F. Hooven.)

Radio Direction Finder (RDF) In early March 1937, before the first World

Flight attempt, Earhart and Putnam removed the Bendix radio compass and installed a Bendix Radio Direction Finder (RDF). They removed the loop antenna (DF) and

housing above the navigator's station and installed a larger loop without housing above the cockpit. They removed the short sense wire antenna

on one side of the fuselage. Some beleive they kept

it. The radio operator would connect the radio receiver to the long receiving

wire antenna (TA) to listen for radio signals and then switch to the loop antenna (DF) to find their direction. The loop antenna indicated the directions of the signals on a baseline. The

baseline was detected by manually rotating the loop antenna - or flying a circle with the plane

- and listening for the strongest points ("peaks") and weakest points ("nulls") of the signals. This was called "taking a bearing".

The weakest point ("null") indicated the directions of the baseline

of the signals. If the signals were strongest when the loop or plane was turned to the north and weakest when the loop or plane was turned to the east, the signals were coming from the east or west. This was called

"getting a minimum". This type of DF was known also as a "null"-type. Finding the "null" or "minimum" could take a minute or more. The direction to the source of the signals was not known. The signals were

coming from one direction or the other - opposite directions - on a straight

180-degree baseline. In most cases, the radio operator on board knew the source of signals could only

be ahead of the plane and not behind it. In some cases, however, a radio operator might not know if the source of

radio signals was ahead of the plane or behind it. The radio signals were coming from one side of the plane or the other.

The plane might have passed it. Once the radio operator detected the baseline of the radio signals, trigonometry

was applied to determine the direction to

the source. The radio operator took a second bearing from a different

point or angle. The point of intersection of the two bearings indicated the position of the source. Removing the radio compass system may have been a mistake. The radio compass

indicated the direction to the source of the radio signals. The RDF system indicated only their baseline. Apparently, the

Putnams were not impressed. Getting a second bearing and finding the direction to

the source of signals by triangulation might take some time but the result should be the same. Earhart claimed the

radio compass, which weighed 30 pounds, was too heavy. This may have been a polite excuse, however. Perhaps it did not work

as well as expected. Money may have been involved. Airfields had radio beacons and RDFs to guide planes. A plane's RDF could

take beatings on a signal broadcast by a beacon to identify its direction. If a plane's radio transmitted a message by voice on the radio telephone or signals in Morse Code by telegraph (usually

the latter) long enough, the operator of the RDF at an airfield could take a bearing on the plane, identify the

direction to it, call it by radio and give it instructions to the airfield.

RDFs were not always accurate. RDFs were known to err, especially at longer

distances. RDFs had to be cross-checked by celestial observations and dead reckoning. That was one reason Earhart and Putnam

hired Noonan for the first attempt of the World Flight. By some accounts, the loop antenna could be used also as an auxiliary

receiving antenna. Its range of frequencies as a receiving antenna is unclear. Some believe the loop antenna could receive

the same range of frequencies as the radio receiver. For direction-finding purposes, however, a loop antenna operated only

on low frequencies on or below 1500 kcs. and worked best within close range of a radio station's transmitter, within perhaps 50

to 100 miles. This was so with the radio compass also. Whatever signals they received, neither could operate on high frequencies or from a great distance. As far as is known, a small loop antenna capable

of taking a bearing on a signal above 1800 kcs. has never been developed. For the second attempt of the World Flight, Earhart planned to broadcast

on 3105 by night and 6210 by day and use her receiver mostly for direction finding. She would broadcast reports and take bearings.

She requested that all communication be in voice over the radio telephone ("In English") and not in Morse Code by telegraph

("Not Code"). In telegrams, Putnam specified that Earhart's RDF operated within a range of low frequencies from 200 to 1400 kcs. Earhart said 200 to 1500 kcs. Either would

be correct. Generally, it is believed its range was 200 to 1430, as for the flight to Honolulu in March. As

noted above, ships at sea, keeping watch for contact requests and emergency distress calls in Morse signals on 500 kcs.,

used low frequencies also for homing in navigation. Most ships had an RDF operating

within a range of low frequencies not higher than 550 kcs.

When approaching, Earhart could contact the ship on 500 kcs. and both could take bearings on another low

frequency, usually around 500 kcs. Whether or not Earhart knew Morse

Code, she could take a bearing on signals sent in Morse or a long tone. She could leave the microphone switch down, producing

a long continuous tone, for a ship to take a bearing on her. Some believe there was a short fixed wire antenna on one side of the plane

solely for 500 kcs. For reasons that are not clear, it was claimed that Earhart's ability

to transmit and receive on 500 kcs. during

the second attempt was reduced and very limited or non-existent. In mid-June, as Earhart

and Noonan flew over India and Burma, Putnam warned that Earhart's 500 kcs. was of "dubious usability". If Earhart could not transmit or receive on 500 kcs., she was unlikely to transmit

or receive on other low frequencies. She would not hear the low-frequency signals in the receiver from a receiving

wire. She would not hear signals on low frequences from the loop antenna and thus she would be unable to take bearings

on low-frequency signals from ships. She would be unable to transmit signals on low frequencies for ships to take bearings

on her. The response from the Putnams' go-between aboard the Itasca, Richard Black: "Try 500 kcs. close

in." That was the general practice. Whatever Earhart may have said on the phone to her husband, she never

indicated in her telegrams that her radio receiver and transmitter on 500 or other low frequencies were faulty or not

performing. If Earhart was without 500 kcs, the radio transmitter and receiver

or antennae were changed or adjusted before departing Burbank or Miami or developed malfunctions en route. If the radio was not changed and

it functioned properly but Earhart could not transmit or receive on 500 kcs., the long receiving wire antenna was shortened or removed and the transmitting V antenna was shortened. If so, Earhart would still receive low-frequency signals by the loop antenna, whcih was connected by

a seperate relay directly to the radio receiver, and she could take bearings on the signals. If the radio receiver could not

receive 500 kcs. or other low frequencies, Earhart could not receive and take bearings on low-frequency signals. If Earhart could not transmit on 500 kcs. or other low frequencies she might not

be able to contact ships at sea.

On

the flight from California to Honolulu in March, Manning took a bearing on signals from a beacon on 290 kcs. as the plane

approached Oahu. The next and second leg of the flight did

not get off the ground. If the flight to Howland had proceeded as planned, Manning would take bearings on signals on 375 kcs.

from Coast Guard cutters stationed on plane guard at Howland and along the way.

Whatever

changes were made to the radio system, by the end of June, Earhart claimed she had a high-frequency RDF. In telegrams, she

claimed its range

of frequencies was 200 to 1500 and 2400 to 4800 kcs.

Whether or not Earhart had in fact a high-frequency RDF with a range

of 2400 to 4800 is not at all certain. Few believe it. Her claim was probably false. But if her RDF was high-frequency,

Earhart could take bearings on radio broadcasts on 3105 kcs. That

may have been to say, however, that Earhart would not have to take bearings on low frequencies. The loop antenna might receive high-frequency signals but for direction-finding

it was limited to low frequencies up to 1500 and worked only within close range of a radio station

transmitter. In close, however, it might work with strong signals in Morse on 3105.

This was perhaps what Earhart had in mind. (Source:

F. Hooven.) After the crash in Honolulu, the plane was repaired in Burbank. Some

had the impression its radio's capability was reduced; this was to be corrected in Miami but further reduced instead. Some believe the Putnams were told the loop antenna might serve as an auxiliary

receiving antenna and assumed it would also take bearings on high-frequency signals. This seems unlikely. Some

wondered if the Putnams were misled by radio technicians who claimed they could reconfigure the RDF system to take bearings

on frequencies above 1500 kcs. This too seems unlikely. Some

believe the Putnams were paid by Bendix to replace one RDF system with a less reliable or non-functioning one in Miami.

The Bendix radio compass, installed earlier, was developed with the US Army. The Bendix RDF was developed

with the US Navy. The navy may have persuaded the Putnams to replace the radio compass with the RDF. Some wondered

if the navy was involved in installing an "experimental" "high-frequency" RDF on the plane. That is possible. There were

such RDFs but their reliability was uncertain. Bearings on high-frequency signals were considered unreliable, especially

beyond their optical range, particularly in the early morning. By

the time the plane reached Lae, Earhart should have known just what her loop antenna could do and could not do. Apparently, she was never able to test it (properly) during the second

attempt. She never got a bearing. A loop antenna was used to receive only. It was not used to transmit. Indeed, the specifications of Earhart's radio system in Lae are not at

all clear. The radio and antennae should have been thus, as on the flight to

Honolulu and as it prepared to fly to Howland in March 1937:

Transmitter (LF and HF) (tunable) (telegraph

and telephone); Receiver (LF and HF) (tunable) (telegraph and telephone; direction finder);

Antennae: 1.

V (Transmitting) atop plane (LF and HF) (fixed); 2. TA (Receiving) under plane - long (LF and HF) (adjustable); 3.

Loop (DF) LF 200 - 1430. For the flight in March from Honolulu to Howland and Lae, which ended

in a crash on take-off, Manning was to transmit and receive messages by voice and telegraph on 3105 by night and 6210 by day.

Over long distances, Mose Code only. In close, 500 - in Morse Code only. Manning would take bearings

on signals transmitted by Coast Guard ships on 375 kcs. (Source: E. Long.) All

things considered, before leaving Lae the plane's radio system was probably thus: Transmitter

(HF or LF and HF) (tunable) (telephone only); Receiver (HF or LF and HF) (tunable) (telegraph and telephone; direction

finder); Antennae: 1.

V (Transmitting) atop plane (HF or LF and HF) (also receiving?) (fixed); 2. (?) TA (Receiving) under

plane - long (LF or LF and HF) (adjustable) or short (HF) (fixed? or adjustable); 3.

Loop (DF?) LF 200 - 1430 (or 1500?) and HF? 2400 - 4800 ("any frequencies not near ends suitable) (also

for receiving? distance?); 4. (?) short wire on side (500 kcs, sense [DF] or HF) (fixed). Earhart

may have left Lae with only: Transmitter (HF) (tunable) (telephone only); Receiver

(HF) (tunable) (telephone and telegraph, direction finder); Antennae: 1.

V (Transmitting/Receiving) atop plane (HF) (fixed); 2. Loop (Receiving [HF])

(range?). The radio logs indicate the plane may have been unable to transmit and receive low frequency signals. The relay from the receiving wire antenna to the receiver may have been faulty and it is possible that only the loop

antenna could receive (Source: A. Gray). The RDF did not work. Some

believe the radio system was adequate and functioning but Earhart did not know how to use it. The additional job of radio

operator may have been too much for her. Some believe the radio system was faulty and inadequate and Earhart did not

care - and her description of it fiction. Earhart

had problems with her radio and RDF throughout the World Flight. This was to be expected of any radio on a

plane at the time. Radios

required frequent adjustments, repairs and changes. On the flight across the Atlantic, from Brazil to Senegal, all radio systems

failed. On the flight from the island of Timor in the Dutch East Indies to Darwin, the

radio did not work. Apparently, a fuse blew. It was replaced and the radio was checked by an army radio techincian in Darwin. On the flight from Darwin to Lae, Earhart was in radio contact with Darwin

but could not contact Lae. Thus, she could not test her RDF as she approached Lae. This was Earhart's fault.

Before departing Darwin, Earhart sent wrong instructions for the use of radio frequencies to Lae.

She wanted to send and receive on 6210. Apparently, in converting the frequency in kilocycles to wavelength in metres she

miscalculated and specified an incorrect wavelength. Thus, Lae did not hear her broadcasts on 6210. She did not hear

Lae. Several days earlier, on Java in the Dutch East Indies, Earhart sent odd instructions to two ships stationed in the Pacific to assist her

in taking bearings. Initially, it was suggested, in Navy telegrams, that the ships could stand by on 333, 400, 545 or other

close frequencies. The Itasca and the Ontario could stand by on 400 kcs. Earhart could contact the ships

on those frequencies. She might also take bearings on those or other low frequencies.

Converting wavelengths into frequencies Earhart gave kilocycles and metres the same number value. Thus, in her instructions to the

Itasca, she changed 400 kcs. - 750 metres - to 750 kcs., and

then, for some reason or other, adding nought, to 7500. In

her instructions to the USS Swan, a naval vessel between Howland and Honolulu,

333 kcs. - wavelength 900 metres - became 900

kcs. and then, again, adding nought, 9000 kcs. (Source: A. Gray.)

The Itasca and the Swan

could receive and transmit on the high frequencies requested by Earhart. The frequencies were within the range of their

radio capabilities. However, radio signals transmitted on high frequencies were less reliable than signals on low frequencies.

Contacting a ship on a low frequency would be better. Taking bearings on such high frequencies was out of the question.

(Source: A. Gray.) Earhart was ill at the time. Were her specifications miscalculations? Did she know what she was doing? The USS Ontario, was to stand by on 400 kcs. The ship had high-frequency, but it was limited to

reception on 3000 kcs. and could not transmit on high-frequencies. Thus, Earhart agreed to 400 kcs. She did not ask the Ontario

to send messages on 7500 kcs.

Did

Earhart intend to take bearings on high-frequency signals? A

loop antenna might receive high frequency signals but it could not take bearings on frequencies higher than 1500 kcs. unless

close to the transmitter and the signals strong. Perhaps on 3105 but certainly not 7500 or 9000.

Earhart's

odd request for contact on 7500 and 9000 was questioned. The commander of the Itasca expressed concern for

the flight's safety.

From

Lae, Earhart asked the Itasca also to send the latest weather reports from Howland to Lae (Guinea Airways radio station)

by shortwave on the 25-metre band (11600 to 12100 kilocycles), or the 46-metre band (around 6500 kilocycles). The Itasca could not transmit directly over such a long distance, something

Earhart apparently did not understand. Earhart

may have come to her senses towards the end of her stay in Lae. In her final instructions to the Itasca, sent twice,

Earhart did not mention 7500. Plane and ship would transmit and receive on 3105 and 6210. Earhart asked the ship to send a

long continuous signal on 3105 as she approached the island. Apparently, she intended to take a bearing on the signal. By

then, however, the commander of the Itasca may have had enough. He replied but did not acknowledge Earhart's request

for a long continuous tone on 3105. The Itasca transmitted on 7500, as requested previously, but never a long tone on 3105. Telegrams make clear that any "radio misunderstanding"

from Lae to Howland was Earhart's. She should have realised this

before setting out. She did not care about the technical matters of radio. Or she was ill. She failed to check with Noonan

before sending her telegrams. It appears that the radio operators for Guinea Airways, the Ontario and the Itasca acted

according to plan. The extent to which the three stations may have been responsible

for radio communication failures is not certain. The Itasca

is often criticised and there are questions about Lae and the Ontario. It is clear, however,

that Richard Black, the Putnams' personal go-between for the next two legs of the flight across the Pacific, did

not make proper and adequate preparations for the use of radio. (See below.) Earhart failed in her first attempt

to reach Howland. Now, Earhart was to try for Howland once more, this time from Lae. The plane on take-off would be

overloaded with fuel, more than it had been in Honolulu. The route was longer. This

time, Earhart was without a radio operator and the radios on board were not very reliable. As

the celestial navigator on Pan Am's Pacific Clipper flights, Noonan worked closely with the radio navigator on board. He understood

radio navigation thoroughly. Initially, two-way radio and the RDF controls were installed in the back of the plane for Manning.

He worked closely with Noonan on the flight from California to Hawaii. When Manning left the flight, his job went to Noonan.

However, Earhart and Putnam had the radio operator's radio and the RDF controls removed from the back and RDF controls reinstalled

in the cockpit. Earhart would control all radio operations herself. No radio equipment was left for Noonan. This was

a mistake. Noonan had far more experience with the radio operations of long-distance flights across the Pacific. Earhart was repeatedly advised of the need for an expert radio operator on board over

the Pacific to handle all radio matters, especially pre-flight preparations and communication in Morse Code during the

flight. Indeed, Earhart

caused the radio communication failure on the flight

from Darwin to Lae before she took off. Did Earhart and Putnam hope to recruit a radio operator and install better

radio equipment before the plane took off from Lae? No radio operator would join a flight that was without 500 kcs., low frequency,

a telegraph set and a reliable RDF.

No

radio operator would go if arrangements with radio operators along the flight path were incomplete

or impractical. Correcting

the situation would require more

money, add weight and prolong the delay. It appears that Earhart was not

counting much on radio communication, if at all. She had made it this far. She believed Noonan would get her the rest of the

way by celestial observations and dead reckoning. Callopy: "Mr. Noonan told

me that he was not a bit anxious about the flight to Howland Island and was quite confident that he would have little difficulty

in locating it." Earhart's

health Earhart was

ill with dysentery five days earlier on Java. Earhart was aware that the "radio misunderstanding" was hers but her telegram

implied that others were responsible. Earhart may have been ill but "personnel unfitness" implied that another was not well.

Perhaps Earhart

meant "personal unfitness". One would

assume that if Earhart were ill - or not feeling well - she would say so.

Perhaps Earhart or the telegraph operator misspelled the word. Otherwise, Earhart's telegram could be considered a display

of poor manners.

Was

Earhart having second thoughts about the flight to Howland? Was she in over her head? Perhaps Earhart never intended to go through with the flight. Was it her

plan all along to terminate the flight in Lae? Was her ground-loop in Honolulu deliberate? Earhart could quit now. Her sponsors would be disappointed. But she had flown

three-quarters of the way around the world and they had gotten something out of it. Indeed, this may have been the reason

for the flight's change of directions for the second attempt, from west to east, and putting off

Howland to the end. So late in the flight, Earhart could not publicly admit that her "Flying

Laboratory" had been ill-prepared from the start. Now, facing the greatest challenge of the flight, she could not

publicly acknowledge that the odds against success were overwhelming. The

Putnams could not fault their sponsors. They could not blame the plane's manufacturer or the designers

and installers of the radios, or civilian and military radio operators along the flight path, or the mechanics who serviced the

plane and technicians who serviced the radios. Had Earhart planned a last-minute excuse to abandon the flight?

Would Earhart claim illness? Would she try to blame Noonan? It would be difficult

to fault a man of Noonan's high professional reputation. Could she pretend that

Noonan was "unfit"? Noonan was in good health.

It appears that someone at

Pan Am plotted to do a dirty job on Noonan in 1936. As chief navigator on all of the airline's Pacific Survey flights across

the Pacific in 1935 and first commercial Clipper flights across the Pacific in 1936, Noonan gained considerable fame. But he was among employees,

led by pilot Edwin Musick, who requested better working conditions and pay for overworked Clipper flight crews. Someone

at Pan Am may have resented that. As

Earhart's navigator, Noonan became world famous. It appears that some close friends and admirers of

Earhart, out of envy or to cover for her, sought to smear him. Decades later, a Hollywooder, Gore Vidal, who was the son of Eugene

Vidal, an intimate friend of Earhart, indicated that this was the Putnams' plan: Fault Noonan, call off the flight in Lae,

and blame him for Earhart's failure to cross the Pacific. Vidal (or his father or a friend of his father) invented a

malicious tale that Earhart telephoned Putnam (in New York City) from India (Calcutta) and later from Lae to complain about

"personnel problems" or "personnel trouble" - and on the phone to Lae, Putnam tried to persuade Earhart

to end the venture and return home (by ship). According

to Putnam, in his book later in the year about the flight, he did not speak to his wife by telephone while she was in Lae.

They corresponded by telegraph. Gore Vidal talked about everything under the sun but seldom made sense. Vidal claimed

the Putnams' telegrams were written in code and Earhart condemned Noonan. Eugene Vidal was a business partner of Earhart. He was often said to have been her long-time lover. He owed

his appointment as one of the government's top aviation officials by President Roosevelt in 1933 to Earhart and owed

his reinstatement by the president in 1935 to her. She could withdraw her political support if Vidal were not reinstated.

Vidal was much involved in the plan to stake out Howland Island for the U. S. and prepare an airfield on the island. He pulled

strings for Earhart until his resignation in early 1936. If

anything, the telegram reveals a duplicitous Earhart who could not be trusted. The stories about it raise questions about

Pan Am, the Putnams and the Vidals. Did Noonan get firm with Earhart after their arrival in Lae? Her last mistake

may have been one too many. Did he see her telegram(s)? Some might consider her telegrams mischief. Some might see her as

a troublemaker. Was Earhart trying to provoke Noonan, to make him quit and provide her an excuse to abandon the flight? There are no credible accounts of disputes between Earhart and Noonan. On

the contrary, pilot and navigator seem to have gotten along decently well. Earhart was a flyer hell bent for leather. She threw caution to the

winds. She valued publicity above all else. That is how some of her contemporaries and later biographers described her. She

did not have a head for technical matters. Noonan was thorough in his planning and in his work. Many maintain that

his contributions to aviation were more significant than Earhart's. Earhart

and Noonan made long and careful preparations for the flight. Should they have gone ahead with the flight? Few, if any, would

have. Some may wonder

if Earhart planned suicide (she said it would be her last venture in aviation) or Putnam plotted his wife's death (he sent

her off without proper radio equipment). Noonan would see the Queen of the Skies through. It is to be regretted that crooks and crackpots drew a false picture of Noonan with misleading accounts and

tall tales and played them up with cheap films. Earhart and Noonan watched maintenance work on the plane throughout the

day, 30 June. Earhart postponed the departure and re-set the take-off for Howland to mid-morning

the next day, 1 July.

To set his chronometers, Noonan had to wait at the

Guinea Airways radio station to receive a time signal from Australia. He did not receive it. A chronometer one second off

can cause a navigation error of ten miles. (There were two or three chronometers on board earlier, in Hawaii, but reports

indicate the plane had only one in Lae.) As mentioned previously, in March,

when Earhart, Manning and Noonan were to fly from Honolulu to Howland, Manning would transmit messages in Morse Code on 500

kcs. when within close range of ships on plane guard. Manning would take bearings on signals from ships on 375 kcs. Putnam said that Earhart's transmitter/receiver

on 500 kcs. was of "dubious

usability". Thus, she might not be able to contact ships on the flight path or take bearings. On 30 June, the radio operator for

Guinea Airways, Harry Balfour, tested Earhart's radio receiver on 500 kcs. Chater: "At noon on June 30th Miss Earhart, in conjunction with our

Operator, tested out the long wave receiver on the Lockheed machine while work was being carried out in the hangar. This was

tested at noon on a land station working on 600 metres." Note:

Long Wave 600 metres = Low Frequency 500 kcs. Apparently,

Earhart's radio receiver received signals on 500 kcs. By which antenna? More than likely, a receiving

wire. Loop? Both? Chater did not say. Chater: "During

this period the Lockheed receiver was calibrated for reception of Lae radio telephone, and this was, on the next day, tested

in flight." "Lae

radio telephone" = Shortwave/High Frequency 6522 kcs. For

legal reasons, Lae could not transmit on 6210. Its use was restricted to the U. S. Thus, Earhart's receiver was "calibrated" to

6522. The next morning, Earhart and Noonan took the plane on a test flight. Chater: "At 6.35

a.m., July 1st, Miss Earhart carried out a 30 minute air test of the machine when two way telephone communication was established

between the ground station at Lae and the plane."

During the test flight, Balfour heard Earhart

on 6210 and Earhart heard Balfour on 6522 kcs. Balfour pointed out that Earhart's transmitter on 6210 was "very rough"

but otherwise "working satisfactorily". Chater: "Our Wireless Operator

reports - 'The condition of radio equioment of Earhart's plane

ia as follows - Transmitter carrier wave on

6210 kc was very rough and I advised Miss Earhart to pitch her voice higher to overcome distortion caused by rough carrier

wave. Otherwise, transmitter seemed to be working satisfactorily.'" The test may have omitted 3105, which was Earhart's night frequency. Earhart

planned to take off from Lae in the day-time. Her day frequency was 6210. Chater's letter repeated an odd mistake. Chater did not mention the frequency 3105. Elsewhere in his letter, Chater twice mentioned the frequency "3104" when referring to 3105.

What about Earhart's RDF? There were questions about it. Did it actually work? Was the loop antenna just for show? It appears that it involved

complicated mechanical procedures. Perhaps too many for a seat-of-the-pants pilot who could not be troubled with such things.

Chater: "The Operator was requested to send a long dash while Miss Earhart endeavoured to get a minimum on her direction

finder. On landing Miss Earhart informed us that she had been unable to obtain a minimum and that she considered this was

because the Lae station was too powerful and too close." One

could assume the test was on 500 kcs. or another low frequency. Chater, who flew Lockheed Electras before

managing Guinea Airways, did not give more specific details. Callopy, Chater, Balfour and Earhart

should have been concerned about a test of the RDF on 500 - or another low frequency from 200 to 1400

kcs. - in flight. The fate of the crew might depend on it. Generally, the closer a loop antenna

was to the source of signals the more reliable it was. But if too close, or if the signals too strong, the loop might not indicate

their weakest point - "get a minimum". Earhart dismissed the problem. She did

not check again. This may have been a serious mistake. Was the bearing, by any chance, taken

on a high-frequency signal? Earhart claimed she had an RDF with two bands - the second band for high frequencies with a range of 2400 to 4800

kcs. Thus, it would be advisable to test the loop antenna on

3105, a frequency Earhart and the Itasca were to transmit

and receive at night. If Earhart failed to take a bearing on 3105 (or "3104") with a high-frequency

RDF there was cause for concern. Given

Earhart's odd radio requests

from Java earlier, one could wonder if the

test was on 6210. (Lae could not transmit on 6210.) A test of the loop

antenna on 6522 (or 6210) would be useless. Earhart would hear the signal but, with an RDF limited to 4800, the loop antenna would not take a bearing on it. Chater did not mention a test of Earhart's transmitter on 500.

Balfour did not test for a bearing on Earhart. Chater mentioned only an unsuccessful test in flight of the loop antenna on an unstated frequency. Earhart postponed the departure to 2 July.

Earhart

and Noonan watched refueling of the plane. Callopy:

"According to Captain Noonan the total fuel capacity of the aircraft was 1150 U.S. Gallons and oil 64 U.S. Gallons." Chater: "After the oil tanks were drained on June 30th the Vacuum Oil Co.

report that they filled into the tanks 60 gallons of Stanavo 120 0il, and this was carried during the test flight before mentioned."

Chater: "July

1st — after the machine was tested the Vacuum Oil Co.’s representatives filled all tanks in the machine with 87

octane fuel with the exception of one 81 gallon tank which already contained 100 octane for taking off purposes. This tank

was approximately half full and it can be safely estimated that on leaving Lae the tank contained at least 40 gallons of 100

octane fuel – (100 octane fuel is not obtainable in Lae)." Callopy: "One tank contained only 50 gallons of its total capacity of 100 gallons. This tank contained 100

octane fuel and they considered the 50 gallons of this fuel sufficient for the take-off from Lae." The other tanks were filled, added to the fuel left in the tanks after the flight from

Darwin and the test flight. Chater:

"A total of 654 imperial gallons was filled into the tanks of the Lockheed after the test flight was completed. This would

indicate that 1,100 US gallons was carried by the machine when it took off for Howland Island." Callopy: "They

left Lae with a total of 1100 U.S. Gallons of fuel and 64 U.S. Gallons of oil." Thus, the plane had about 1,100 US gallons before take-off and about 1,050

gallons after take-off. The required fuel reserve

was probably 20%, or 210 gallons of the total, or

25% for 262.5 gallons, after take-off. There are numerous reports on the plane's flight

limit (endurance) with 1,050 gallons of fuel. Some claim the plane could fly at least 30 hours or more with no headwinds ("in still air") at a cruising speed of 130 knots. An average fuel consumption rate of about 50 gallons per hour in often mentioned in accounts.

Thus, Earhart would have fuel for 21 hours. A 17-hour flight would consume 850 gallons, leaving 200 gallons for four additional

hours of flight. An 18-hour flight would consume 900 gallons of fuel, leaving 150 gallons for three more hours of flight.

A 19-hour flight would consume 950 gallons, leaving 100 gallons for two more hours of flight. However, fuel consumption varied from 38 to 60 gph depending on the rate of climb,

engine RPM, the weight of the plane, temperature, altitude and hours aloft. After six to eight hours of flight and with a

lighter plane, consumption could be reduced to 38 or 43 gph if the

plane maintained an altitude of 10,000 feet - or 8,000 feet in the tropics. Thus, more flying time. But Earhart and Noonan

would not have the best of weather. Earhart had the latest weather forecasts, from the US Navy's air base in Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, issued

on the previous day, Wednesday, 30 June, for Thursday, 1 July. Guinea Airways received the forecasts that day, on 1 July. About half-way along Earhart's flight path to Howland, the USS Ontario was

stationed to signal the flyers. The

forecast from Lae to the Ontario was for partly cloudy skies with rain squalls

250 miles east of Lae with 12 to 15-knot winds from the east-south-east. The forecast for the flight path from the Ontario to the Gilbert

Islands was for partly cloudy skies with cumulus clouds at 10,000 feet and 18-knot winds from the east-north-east. For the rest of the flight path, from the Gilberts to Howland, the

forecast was for partly cloudy skies with scattered heavy showers and 15-knot winds from the east-north-east. The forecast warned avoiding "towering cumulus clouds and squalls by detours

as centres frequently dangerous". By some accounts, initially, Earhart and Noonan

expected the flight to Howland to take 17 hours. By the latest weather forecast, they probably planned

to make a detour from a direct flight path to avoid the rain squalls over the island of New Britain and the Solomon Sea. The detour would add distance to the flight. Taking also

the forecast headwinds and quartering winds into account the flight could take 18 hours. Some reports mention 19 hours. The

plane would need enough fuel to return to Lae if at any point Noonan was unsure of reaching Howland. Half-way through its

fuel supply, probably after nine to ten hours of flight, the plane could turn back to Lae. Less than half-full, or more than half-way to Howland, Noonan might have

to count on tailwinds to get the plane safely to Lae. Earhart and Noonan wanted to reach Howland at sunrise. They would have to take off from Lae by 10:00

a. m. the next day. Flying by night, if the skies were clear, they would have the moon and stars to guide them. Noonan

plotted his chart before the flight and he would look for certain stars, planets and constellations at certain points and

times to estimate his position. If the weather was good, they should have clear radio communication. Noonan was accustomed to long flights across the Pacific. Earhart

had flown non-stop flights of 18 1/3 and 20 2/3 hours over the sea. Pilot and navigator would keep constant watch on

fuel, engines, speed, winds, and heading.

There would not be an idle moment. Earhart's last dispatch, sent by telegram from Lae late on 1 July: "We commandeered a truck from the manager of the hotel and, with Fred Noonan

at the wheel, because the native driver was ill with fever, we set out along the dirt road. We forded a sparkling little river,

which after a heavy rain so common in the tropics, can be turned into a veritable torrent and drove through a lane of grass

taller than the truck. We turned into a beautiful cocoanut grove before a village entrance . . ." Noonan did not receive a time signal from Australia until 10:20 (or 10:30)

p. m. on 1 July. He found the chronometer to be three seconds slow. Earhart and Noonan were at the airstrip at 5:30 a. m. on 2 July. Noonan received a time signal from Saigon at 8:00 a. m. to check again

his chronometer, which was running well and on time. Whatever

arrangements Earhart made with radio operators in the Pacifc, she left them all with Harry Balfour. Before departing Lae,

Earhart gave Balfour her radio facility book. The book contained many papers and all of her telegrams with instructions for

radio communication with radio operators along the flight path across the Pacific. Earhart also gave her pistol or revolver and ammunition to Balfour. Some

thought the gun was her Very pistol (flare gun). But this is not so. According to Chater, Earhart took the radio station's weather reports of 1 July and also its only copies.

Earhart and Noonan with a chart showing

their planned route across the Pacific. Photo taken in the US in May 1937. Before

setting out, Earhart requested that all radio communication follow Greenwich Civil Time (GCT). Not local zone times. GCT was

the same as Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). Midnight at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, England = 00:00 GCT and GMT.

Earhart and Noonan took off from the turf airstrip in Lae at 10:00 a. m.

local time on Friday, 2 July, on the 30th leg of their flight. There were reports that the plane took off after 10:00

- as late as 10:20 a. m. Lae was ten hours ahead of GMT. Thus, the take-off was at 00:00 GMT on

Friday, 2 July 1937 (10:00 a. m. in Lae). Note that in this case GMT = Elapsed